Gainsharing or Profit Sharing:

The Right Tool for the Right Organization

by Robert L. MasternakMasternak & Associates

Liberty Tree Plaza

1114 North Court, Suite 195

Medina, Ohio 44256

Phone: (330) 725-8970

masternak@zoominternet.net

Copyright © 2009; Masternak & Associates; All rights reserved.

Reprinted here with permission.

Many people who confuse Profit Sharing and Gainsharing view them as being one in the same. I find that many companies that install a Profit Sharing have selected the wrong tool and quickly become disappointed that they have been unable to foster a change in behaviors and to drive organization performance. The purpose of this chapter is to explain the similarities in Profit Sharing and Gainsharing, their differences, the primary purpose for both system, and why Gainsharing is often the better tool. The chapter begins with a fairy tail about a farmer’s well founded intension gone a rare. The story may be familiar to some and may proof to be insightful to others.

Story:

Once upon a time there was a farmer in the land of Michigan who held his workers in high regard. He appreciated their dedicated service during the hot and dusty summer days and the cold and dampness of the November corn harvest. He respected their efforts and wished to recognize them for their part in the farm’s success. He knew that without them he would not have been able to enjoy the prosperity and pride that he had in his highly successfully farm. He had often thought about ways he could recognize them for their efforts. Yes, it was true that he had the annual harvest feast, but that did not seem to be enough.

He had heard of another successful farmer in an adjacent land who had recently installed a profit sharing plan in order to share the financial gains with his workers. So the farmer went there for a visit and then came home to put together his own, very simple and understandable profit sharing plan. Basically, the farmer calculated his total revenue from a variety of sources, including the sale of grains, livestock, land leasing, and produce sales at the local farmer’s market. From his revenue, he subtracted all expenses including: the cost of seed, fertilizer, labor, fuel, attorney fees, insurance, depreciation, etc. His result, he called “the bottom line.” Then in turn, he designed a formula to share a portion of the profit pie with his workers. He announced the good news of the newly designed profit sharing plan at his annual year-end feast and handed out bonus checks to the workers equal to 6% of their annual pay. The average check amounted to $1,200, ($20,000 annual compensation x 6%). The workers were delighted with the unexpected bonus and rejoiced in the farmer’s generosity.

The farmer explained to his employees that there would be more of the same next year, if the farm continued to prosper. The workers’ spirits were high, and they eagerly looked forward to the second plan year.

In year two, the farmer made a strategic decision to plant his entire farm in corn, since the price of corn in that land had skyrocketed to $3.00 per bushel, a record level. The farmer foresaw a great opportunity for increasing production and resulting profits. The farm hands worked especially hard planting, fertilizing, cultivating, and irrigating the corn. As a result of their labors that fall the corn harvest yielded a new record, 200 bushels per acre. The extra irrigation and cultivation had paid off! Unfortunately, other farmers also had decided to place all their land in corn as well. That season’s corn production all over the land was at a “bumper year” level. As a result, the selling price plunged to $1.00 per bushel, and the farmer’s profits fell to half of the previous years. At the annual harvest feast the farmer passed out the bonus checks, this time only 3% of compensation. His people were greatly disappointed, but after all, some money was better than nothing. The workers forgave the farmer and looked forward to a better third year.

In year three, the farmer made several strategic business decisions. He acquired more land and decided to boost productivity by investing in a new John Deere tractor. He bought a new truck as well. The tractor was the largest and newest on the market, and he thought it would most likely lead to higher land productivity. The truck was a “4 by 4” with a leather interior and all the added accessories. He knew that the truck was excessive, but after all, he had worked so hard all those years and knew the fancy truck was something he very much deserved. He rejoiced when the bank offered an attractive low interest rate on three loans for the land, tractor, and truck. As luck would have it, however, the new loans had several strings attached, including a variable rate and prepayment penalties. In addition more workers needed to be hired to help with the cultivation and harvest that year, and the spring planting had been especially hectic.

The old workers enjoyed driving the beautiful, new tractor and managed to do some added cultivation. The new workers weren’t as nearly impressed, since they had never once experienced the discomfort and excessive noise of the older, retired model.

By the end of that fateful year, corn production doubled the previous year’s level. The workers grew excited because they had never seen so much corn. Unfortunately, during the course of the year interest rates had taken a dramatic turn. The truck and tractor loan had initially been at only 2%, but during that year the loans soared to 12%. The new variable rate on the land was so excessive that the farmer had to refinance to a fixed rate, resulting in sizable prepayment penalties and costly refinancing charges. He talked to the workers about some of these problems, but they weren’t that interested. Their focus was on better corn yield, cultivation, and irritation.

By the end of that disastrous year, profitability had tumbled to “break-even.” The farmer’s investments had had a devastating effect! At the annual harvest feast, the workers eagerly looked forward to the announcement of the bonus results, but the farmer said, “Woe is me; I have bad news.” Instead of checks, the farmer handed out a copy of the dismal financial results. All of the workers were extremely disappointed. The new workers were especially unhappy. They had been told so many good things about the farm from the human resources manager when they had first been hired. All the workers bitterly complained about the farmer’s extravagant purchases and poor financial decisions. They were especially unhappy when they saw the farmer driving his new fancy truck. Employees claimed they had no control over the farmer’s shortsighted decisions. Attitudes and level of trust declined. Some workers even became bitter and resentful, grumbling and plotting against their hapless employer.

The moral of the story: There are many lessons to learn from the farmer’s story. The farmer’s intentions were very noble, but the results lead to an undesirable outcome. The farmer failed to thoroughly consider what he was trying to accomplish by installing a profit sharing plan. What was the farmer’s purpose for the plan? What did he want to accomplish? Was the objective to drive operating performance (yield) or to help instill in the workers the concept of “common-fate?” Was he primarily interested in providing a monetary reward to motivate employees in their efforts, or was he more interested in providing a benefit to recognize loyalty and service. Also, the farmer failed to consider the appropriate rewards system for the culture, growth, and demographics of his workforce. The farm had grown considerably, adding a number of new workers. Unfortunately, the farm had gotten so large that the farmer didn’t even have the opportunity to meet many of them. Perhaps, he should have talked to more than one neighboring farmer before he jumped into profit sharing. He had heard about a few farmers in other counties who had Gainsharing plans for their workers. However, he didn’t take the time to investigate the Gainsharing concept, thinking that profit sharing was basically the same. Employees have an opportunity to earn a financial reward under both approaches. However, the farmer didn’t recognize that that was where the similarity ends. If he had researched the history and evolution of both approaches and their intended propose, he might have avoided his ill-fated good intentions.

Profit sharing

History: Profit sharing certainly is not a new concept. One of the first documented profit sharing plans in the United States was introduced in 1794 at New Geneva, PA, Glass Works. At the time the company was recognized by the Secretary of the Treasury under Presidents Jefferson and Madison as applying “the nation’s fundamental democratic principles to an industrial operation. However, profit sharing arrangements were far from prevalent until the end of the Civil War. As America became more industrialized, profit sharing begin to grow through the 1920’s. Profit Sharing companies held the belief that sharing profits would unite workers and management in the pursuit of the same common goal. In addition, profit sharing was offered as a means to discourage unionization, but after the Depression through the 1930’s many of these profit sharing plans were discontinued.

After World War II there was a rebirth of profit sharing. Most of these plans were deferred compensation plans driven by the desire to avoid a tax on excess income that had been imposed during the war. In other words, companies would place a portion of the profits aside to fund employee retirement plans. This was especially popular among private, “family” owned companies that saw employees as an extended family. The concept was also one of “common fate.” In good times a family would be able to share more, in the bad times, less. Employees often spent their entire working career with the same company. There was mutual loyalty on both the employer’s and employees’ behalf.

In the late 1980’s some companies attempted to deviate from the deferred compensation nature of Profit Sharing. In other words, Profit Sharing was viewed as incentive compensation rather than a benefit plan. One of the best documented examples was at Dupont’s fibers division which employed approximately 20,000 people. The plan’s designers intended to develop a “program to reward employee contributions, in the belief that sharing the rewards as well as the risks of the division’s financial performance would help the business succeed in the market place.” The complex arrangement focused on “world-wide after-tax operating income and established a “Compensation Target Rate” and a “Variable Element Rate.”

Basically, DuPont’s new pay concept was that employees would place a portion of their normal base compensation at risk. In return employees had the opportunity to more than offset the “at-risk” monies through a year-end bonus. On the other hand, if profitability was significantly below targeted levels employees would loss the monies “at-risk.” The plan could yield a bonus of up to 12 % of salary in an exceptional year. In a bad year an employee could loss as much as 6% of salary. The new “pay-at-risk” system would enable the company to better manage costs by moving to more of an “ability to pay” approach. In addition, the thinking was there would be less work force pressure for base salary adjustments. The theory was that since employees would be sharing in the profits, they would feel and act more like stakeholders. The result would lead to changes in behaviors and work habits, resulting in even more profits.

When the plan was rolled out in 1989, DuPont employees saw a modest bonus after the first year. However, the second year saw rapidly declining profitability. Profits had declined due to a number of unforeseen business conditions, two of which were the rapid increase in raw material prices and the erosion in the final product’s selling price. Profits were “squeezed.” As a result employees lost the portion of their base pay that was placed at-risk. The employee loss represented approximately 4% of compensation. DuPont experienced a significant rise in employee discontent. Some felt that they were “hoodwinked.” A company executive commented, “Employees were not ready for such a program. Employees felt it was fine when they were getting money back, but thought it was not fair when no bonus was paid.” As a result the program was quickly abandoned.

The flaw in the “pay-at-risk form of profit sharing” was that employees were asked to put a portion of their pay in jeopardy over something they had little or no control, profitability. In addition DuPont is a large, world-wide organization. Obviously the sense of employee ownership and identity toward a very large corporation often is found to be less than in a small family-owned company. People have more difficulty trusting the financial data. Clearly most DuPont employees didn’t like putting their base pay at “risk” in exchange for the opportunity to share in the profits. Many would say they “preferred to lose money at the casino; at least they would have had some fun and excitement in doing so.”

In more recent times, “cash,” profit sharing plans have been installed where no “pay-at- risk” is involved. These plans are designed to include all employees including hourly and salaried, non-exempt employees, not just executives and managers. In other words, all employees have an opportunity to share in the profit pie by having an opportunity to receive a year-end cash bonus.

Figure 1

When profits are up, “I get more.” If profits are down, there’s no consequence. Companies that install these plans hope to enable employees to share in the organization’s success, to motivate workers to improve profits, and in turn to act in the best interest of the company.

Unfortunately many companies that have a “cash” profit sharing plan find that workers view the system as an entitlement. People are happy when they get a bonus and are upset when they don’t. Employees feel that when they receive a profit bonus they “earned it.” When they don’t, “it’s the company’s fault.” In lean years, the employee response is too often complaining, whining, and mistrust in the company.

What would the farmer have learned from these experiences?: The clear and simple issues are that for most organizations Profit Sharing plans provide very little or no “line-of-sight” in terms of what employees do and what they are paid. The general employee population has little understanding of how they directly impact a broad financial measure of profitability. Even those who have an understanding of the financial data find their efforts insignificant in relationship to key management decisions and external market conditions. To make matters worse, some may feel that the company may manipulate the numbers in order to take advantage of tax regulations or influence the investment community. These feelings are further exaggerated in large multi-location organizations where employees are distanced from top management. Also these multi-site organizations may calculate profit company-wide rather than on a location-by-location basis.

So should the farmer further consider Profit Sharing? It depends on the objective. If the focus is to share the organization’s success and to reinforce a sense of ownership, then profit sharing might be the appropriate answer. However, the farmer needs to clearly understand the result will most likely be in terms of impacting employee attitudes rather than driving behaviors. This is especially true in organizations that have an absence of a high degree of employee involvement.

If Profit Sharing is the route, should it be a compensation system or should it be designed to be used as a benefit plan, a method to help finance employee retirement years? In most cases history has demonstrated that the farmer may be better served to incorporate Profit Sharing into a retirement scheme. In doing so, employees would see their retirement security grow in tune with the company’s growth and prosperity. In other words, both employee and employer would share in a “common-fate.” This would certainly satisfy the objective of sharing in the organization’s success. The plan would give employees more of a long term outlook and strengthen the sense of identity and ownership. On the other hand, if the farmer’s objective is to influence not only attitudes but to change behaviors, in terms of teamwork, involvement, and communications, profit sharing most likely will be the wrong answer, particularly if the organization has more than a handful of employees.

Gainsharing

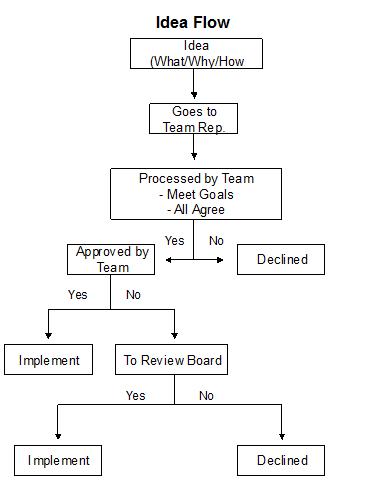

Figure 2 |

In order to fully understand the concept, one must examine its roots. The Gainsharing concept dates back to the 1930's when a labor leader, Joe Scanlon, preached that “the worker” had much more to offer than a pair of hands. The premise was that the person closest to the problem often has the best and simplest solution. Moreover, if the worker is involved in the solution, most likely he or she will make the solution work. Scanlon is often credited for developing a system that promotes involvement in the workplace through employee ideas and suggestions.

Figure 3 |

The involvement structure not only is intended to encourage participation but also is meant to enhance two-way communications regarding company goals and objectives. The idea system helps foster respect and cooperation. In other words, if employees feel their ideas are listened to, are given prompt feedback, and see their ideas promptly implemented, they will feel that they are respected.

Unlike a traditional suggestion system, Scanlon’s system does not provide individual monetary rewards for improvement ideas. The thinking is that the review, investigation, and implementation of employee’s ideas are truly a collaborative effort. Suggestion systems that pay individual awards based on the projected savings from the idea promote behaviors in which employees may conceal their improvement suggestions rather than freely share and collaborate with others to advance the idea. Originally the Scanlon approach didn’t have an employee bonus component. However, a few years after the plan’s initial implementation, Scanlon devised an organization-wide bonus formula that provided a more frequent and line-of-sight measurement system than profit sharing. The idea system and other improvement efforts drove the performance measures, and in turn gains (savings) generated through the measurement formula are shared with everyone in the organization. Basically the Scanlon philosophy says, “As we work together to improve the operations, everyone shares financially in the savings.”

The Scanlon Plan became know as “a frontier in labor-management cooperation.” Scanlon went on to work at MIT to help other labor leaders and managers. As a result the Scanlon message gradually began to spread. In the 1950’s Scanlon developed a group of disciples including Frederick Lesieur and Carl Frost. As companies moved forward with the concept, interest in academic and government circles grew. One of the earlier studies was done by the General Accounting Office and was entitled “Productivity Sharing Programs; Can they Contribute to Productivity Improvement?’ The 1981 study examined 36 “productivity sharing” firms. The GAO reported that “while productivity sharing plans are not the panacea for every firm in the solution to the Nation’s economic problems, they warrant serious consideration by firms as a means “of stimulating productivity performance, enhancing their competitive advantage, increasing monetary benefits to their employees, and reducing inflationary pressure.” The report was published in the hope of encouraging organizations to implement performance-enhancing tools that better engaged the workforce.

As time passed, the term “Scanlon Plan” evolved to “Gainsharing Plan”. The Scanlon term mistakenly had become associated with a single bonus formula focused on people productivity. The “Gainsharing” term became more associated with the use of tailor-made measures that still focused on the line-of-sight.

Another hallmark study was published in 1992. The study, (one of the most comprehensive studies up until that time) was sponsored by WorldatWork (Formerly the American Compensation Association). The group was known as the Consortiums for Alternative Reward Strategies Research (CARS). The study entitled, “Capitalizing on Human Assets,” focused on 2,200 organizations with performance-based reward plans. The findings reported many positive results in both operational performance and employee attitudes. In addition, the study reported better performance in plans that used more line-of-sight measures (Gainsharing) than plans using only “a bottom-line’’ profit- sharing measure. In addition the study reported that successful plans lead rather than support cultural change.

In the mid-1990’s the Total Quality Management movement led to further interest in the Gainsharing concept. As TQM attempted to involve the workforce, employees began asking; “What’s in it for me?” Gainsharing was one answer. More recently interest in Gainsharing has again surfaced as companies cycle through Lean Manufacturing and Six/Sigma initiates. An important point is that all of these improvement initiatives are nothing more than tools to better engage the workforce and to promote involvement. Simply put, these tools are an extension to what Scanlon had preached in the 1930’s.

Unfortunately many of today’s companies that study Gainsharing see the concept as an incentive, thinking that if you simply put a carrot in front of people, you will put “fire in their belly.” These organizations focus on the bonus/incentive side of Gainsharing, and may lack the understanding and appreciation of the cultural and employee involvement origins of the concept. They believe that a bonus system lacking employee involvement, will somehow miraculously lead to a positive result. The problem is that they are putting the cart in front of the horse, the incentive in front of the involvement.

Line-of-Sight & Measurement

Figure 4 |

As the pie expands, the greater the improvement (gain), and the more financial benefit for the company and employees. The key point is that there must be an improvement before any sharing occurs. A critical point is that since gains are typically measured in relationship to a historical baseline, employees and the organization must change in order to generate a gain.

A multi-measure system is commonly used which is referred to as a “family of measures” approach. Basically the “family of measures” approach uses 3 to 6 drivers of performance. Examples of measures are listed below.

| Examples of Operational Measures |

|---|

|

Productivity Equipment efficiency Cycle time Yeild Shrinkage Scrap Rework Spending On-time Shipments RMAs Fill Rate PPM Returned Uptime Inventory Turns Inventory Accuracy Safety Schedule Attainment Energy Usage Customer Complaints Service Satisfaction Spending Credits Collections |

It’s very important to point out that employees do not have 100% control of any measure. No matter what the measure: productivity, cycle time, yield, spending, or on time delivery, there are always outside factors that will influence the result. The point is that employees have more control of operational measures than profitability.

However, unlike Profit Sharing and depending on the Gainsharing plan’s design, employee payouts can potential occur even during periods of profitability decline. Companies with this type of Gainsharing model argue that even though profits may be down, profits would have further declined if not for the savings generated from the gainsharing measures. In this example the company is sharing “savings” and not necessarily “profits.”

Family of measures

Figure 5 |

On the other hand, a Profit Sharing plan may exclude lower level or hourly employees, or profit bonuses may be paid out on a hierarchical basis. In other words the bonus payout percentage is reduced as the Profit Sharing cascades down the organization. The end result could divide the workforce and create feelings of inequity rather than build teamwork and the sense of unity. On the other hand, Gainsharing plans are designed to distribute gains based on an equal percentage of pay or cents per hour worked.

Another Gainsharing line-of-sight enhancement is that Gainsharing is always paid in the form of a cash bonus. Gainsharing’s intent is to be based on the “pay-for-performance” concept as compared to a “benefit/deferred compensation plan.” In addition the frequency for possible payout is greater for Gainsharing than Profit Sharing. The payout of Profit Sharing plans is typically an annual arrangement.

On the other hand, Gainsharing typically has the potential for a monthly or quarterly payout opportunity. A gain and resulting payout is best described as a score rather than a bonus. Since everyone in the organization is typically included, the score is a “team score” as compared to an individual one. The score helps give a common focus for employees on measures they can influence and control. Therefore, Gainsharing works best in work environments that require collaboration between individuals, work groups, and departments.

Another important feature regarding Gainsharing is that typically a portion of the employees share is placed in a year-end reserve account that is paid to all the eligible participants at the end of each plan year. In periods of deficit performance, the employees’ share of the loss is deducted from the annual reserve account. In other words, employees will see consequences for worse performance and longer-term thinking is reinforced. If at the end of the plan year the reserve is negative, a company will typically absorb the loss and start the next plan year at zero. The reserve concept helps further develop a sense of employee identity and ownership to the organization. For example if a company measured scrap and shared 50% of the gain and 50% of the loss (through the reserve) in a sense employees would own 50% of the financial value of the scrap. Obviously the sense of ownership would drive many new behaviors.

Unlike Profit Sharing in multi-site operations, Gainsharing is typically site specific. The measures and resulting gains are specific to the facility rather than gains being aggregated from multiple locations and in turn distributed across the organization. Again the concept is to increase controllability and the line-of sight. On the other hand, unlike group incentives, Gainsharing typically measures across department/units/functions. The concept is to build cooperation and communications between departments instead of building silos.

Another distinction between Profit Sharing and Gainsharing relates to the method of plan design and development. A Profit Sharing plan is typically developed at the top of the organization. In larger corporations the plan may be designed and developed by compensation executives who in turn are granted approval from an executive committee made up of board members.

However, the development of a Gainsharing plan often involves employees in many aspects of the plan’s design and implementation. Often a cross-functional Design Team is assembled that mirrors the makeup of the total organization. The Design Team sorts through a number of issues related to measures, policies, and communication. After upper management’s approval, the Design Team is responsible for conducting all employee kick-off and promotional meetings. The objective is a sense of employee ownership for the plan. In a sense the Design Team members become disciples of the plan and help lead a process for improvement and change.

So should the farmer consider installing a Gainsharing plan rather than profit sharing? Again, the same question must be asked. What is the objective? If the farmer’s objective is to drive organizational change by influencing attitudes and behaviors, then Gainsharing may be the right answer. However, the farmer needs to have the horse in front of the cart. He needs to understand that Gainsharing is an employee “involvement system with teeth.” Simply instituting some type of bonus formula is not enough. A second question; “Should the farmer consider a broad financial measure of performance or more narrow operational measures?” All other things being equal, the use of more narrow, “line-of-sight” measures will more likely yield significant changes in behaviors which in turn generate positive results. The use of a broad financial based measure is much more dependent on the level of employee involvement in the organization at the time of the plan’s implementation. In other words, “How open is the company’s communication? How knowledgeable are employees about the business conditions? What is the level of trust? How much baggage is the organization carrying from its past? A Gainsharing plan that uses a broad financial measure such as profitability, EBIT, or ROI may be a success if the organization can answer “yes” to the following questions: Is their a high level of company commitment to the concept of sharing? Are employees afforded regular training both in terms of skills and individual development? Is communication ongoing? Are the financial results openly shared? Does the company practice open book management? Are managers willing to admit mistakes? Is the workforce highly engaged? Are people at all levels involved in some decision making? Do employees have a strong understanding of how they influence profitability? Do people identity with the business? Does the company demonstrate loyalty to the workforce? Do employees view themselves as stakeholders? If the answers are” yes”, then measuring and sharing profits may work. If not, then it’s best to have a plan that focuses on operational more “line-of-site measures. Otherwise, the organization will find itself in the same position as the generous, but disappointed farmer.

Gainsharing |

Profit Sharing |

|

| Purpose | To drive performance of an organization by promoting awareness, alignment, teamwork, communication and involvement. | To share the financial success of the total organization and encourage employee identity with company success. |

| Application | The plan commonly applies to a single facility, site, or stand-alone organization. | The plan typically applies organization-wide; companies with multiple sites typically measure organization-wide profitability rather than the performance of a single site. |

| Measurement | Payout is based on operational measures (productivity, quality, spending, service), measures that improve the ?line of site? in terms of what employees do and how they are compensated. | Payout is based on a broad financial measure of the organization?s profitability. |

| Funding | Gains and resulting payouts are self-funded based on savings generated by improved performance. | Payouts are funded through company profits. |

| Payment Target | Payouts are made only when performance has improved over a historical standard or target. | Payouts are typically made when there are profits; performance doesn?t necessary have to show an improvement. |

| Employee Eligibility | Typically all employees at a site are eligible for plan payments. | Some employee groups may be excluded, such as hourly or union employees. |

| Payout Frequency | Payout is often monthly or quarterly. Many plans have a year-end reserve fund to account for deficit periods. | Payout is typically annual. |

| Form of Payment | Payment is cash rather than deferred compensation. Many organizations pay via separate check to increase visibility. | Historically profit plans were primarily deferred compensation plans; organization used profit sharing as a pension plan. Today we see many more cash plans. |

| Method of Distribution | Typically employees receive the same % payout or cents per hour bonus. | The bonus may be a larger % of compensation for higher-level employees. The % bonus may be less for lower level employees. |

| Plan Design & Development | Employees often are involved with the design and implementation process. | There is no employee involvement in the design process. |

| Communication | A supporting employee involvement and communication system is an integral element of Gainsharing and helps drive improvement initiatives. | Since there is little linkage between ?what employees do? and the ?bonus,? there is an absence of accompanying employee involvement initiatives. |

| Pay for Performance Plan versus Entitlement | Gains are generated only by improved performance over a predetermined base level of performance. Therefore, Gainsharing is viewed as a pay-for-performance initiative. | Profit sharing often is viewed as a entitlement or employee benefit. |

| Impact on Behaviors | Gainsharing reinforces behaviors that promote improved performance. Used as a tool to drive cultural and organization change. | Little impact on behaviors since employees have difficulty linking ?what they do? and their ?bonus.? Many variables outside of the typical employee?s control determine profitability and the bonus amount. |

| Impact on Attitudes | Heightens the level of employee awareness, helps develop the feeling of self worth, builds a senses of ownership and identity to the organization. | Influences the sense of employee identity to the organization, particularly for smaller organizations. |

2. Masternak, Robert. L. and Camuso Michael. A. “Gainsharing and Lean Six Sigma – Perfect Together” WorldatWork Journal, First quarter 2005.

3. Masternak, Robert. L. "Gainsharing Programs at Two Fortune 500 Facilities: Why One Worked Better." National Productivity Review, Winter/1991/92.

4. Masternak, Robert. L. “How to Make Gainsharing Successful: The Collective Experience of 17 Facilities” Compensation & Benefits Review, September / October 1997.

5. Lesieur, Fredrick G. The Scanlon Plan A Frontier in Labor-Management Cooperation, Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1958.

6. McAdams, J. L. and Hawk, E. L. Capitalizing on Human Assets: The Bench Mark Study, Scottsdale: ACA. 1992.

7. General Accounting Office. “Productivity Sharing Programs Can They Contribute to Productivity Improvement” U.S. General Accounting Office AFMD- 81-22, March 3, 1981.

8. Coates, Edward. M. Profit Sharing Today: Plans and Provisions, Monthly Labor Review, April 1991.

9. Achievement Sharing… In Business Together, DuPont Handbook, 1989.